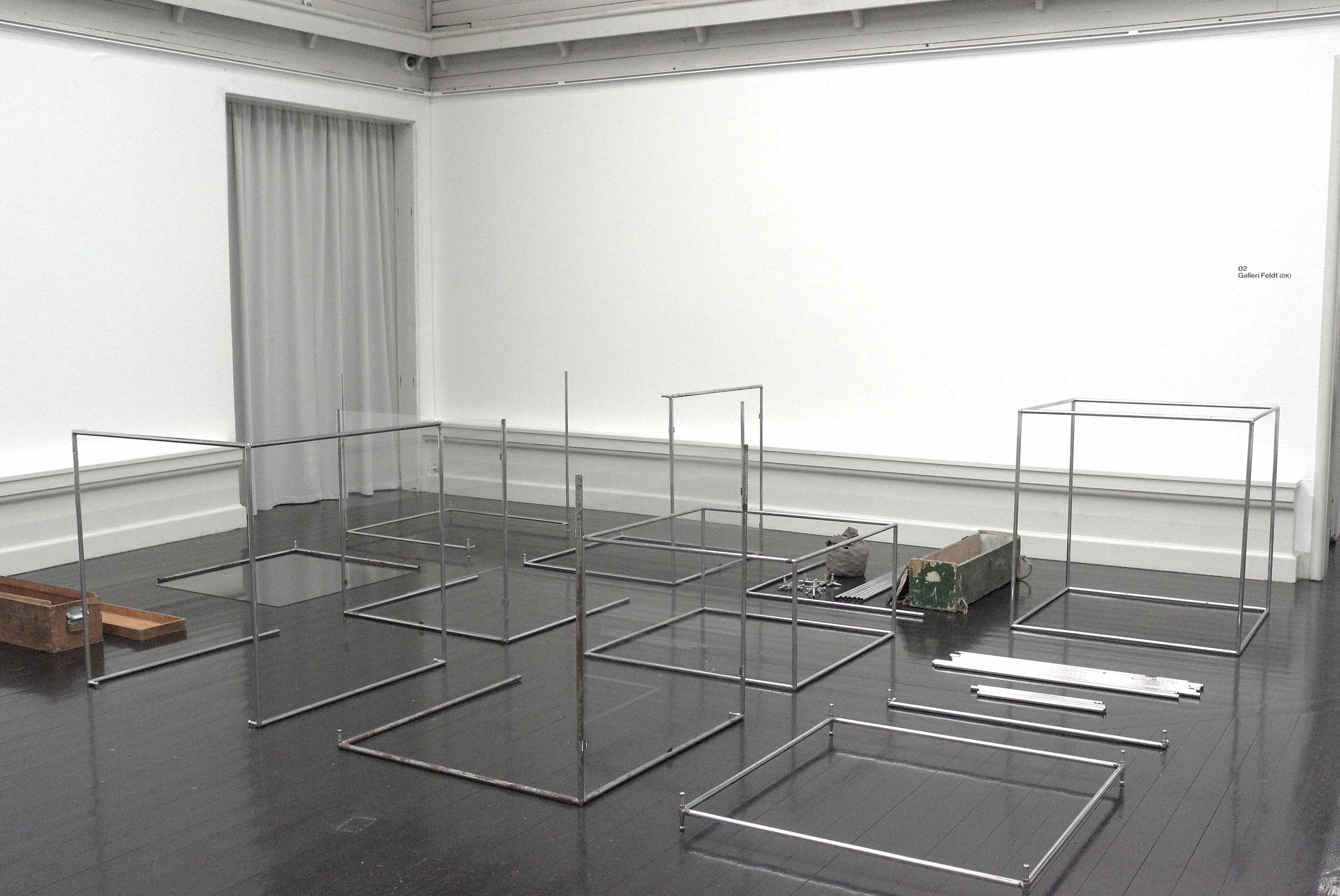

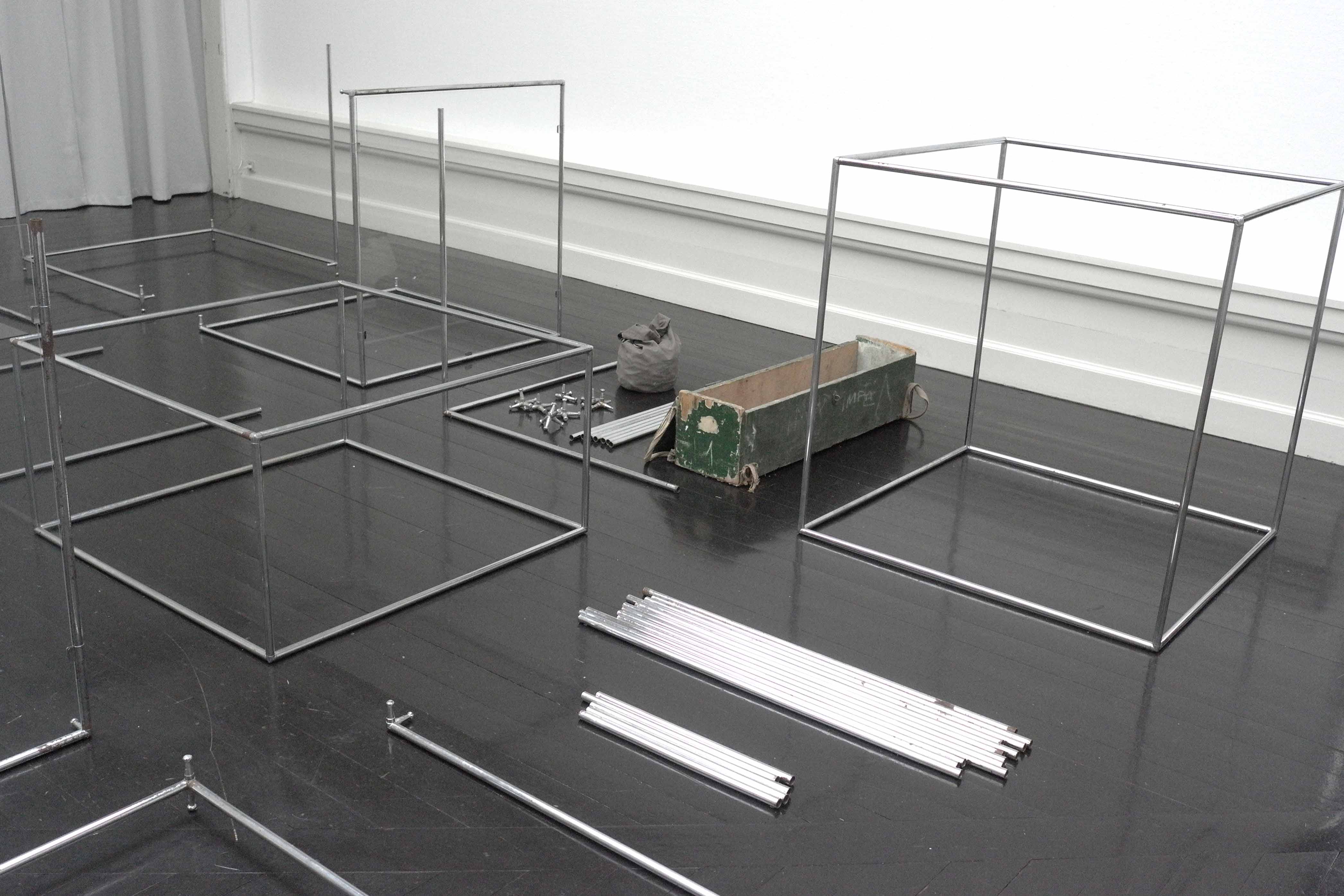

For Chart 2018, Galleri Feldt is proud to present an installation by contemporary artist Kasper Akhøj, whose research-based art has often examined the residual histories of modernist design and architecture in subtle and thought-provoking ways. The Chart 2018 installation is the culmination of a project twelve years in the making, and is composed of a group of structures assembled together from pieces of a modular display system that Akhøj has collected over several research trips in the former Yugoslavia. Enfolded in his works is a complex history with far-reaching implications for how we understand the relation of design to culture, politics, economics, and memory.

The project originated during a 2006 journey through the Balkans, when Akhøj began noticing the display system in places that appeared hardly changed since the early ’90s: small shoe shops in Skopje, a museum in Ljubljana, a state-owned department store in Belgrade. Intrigued by what he described as a “complex network of chrome and colored metal which seemed to have been ever‐present during communist times,” he returned a year later to retrace his previous route and collect pieces of the system, figuring that its modularity would allow him to construct something new out of them.

Although—or perhaps because—it was ubiquitous during socialist times, Akhøj found it very difficult to find information about the system and source parts of it. It was unremarkable to the point of near invisibility, and no widely shared cultural story was attached to it. People knew it by many names—the most common being Salamander, Investa, and metalni police (metal shelf)—or by none. Even state-owned factories that used to manufacture the system (they are now either defunct or privatized) were unaware of ever having done so.

Akhøj’s sources told him that the display system was produced in various regional factories in the 1970s and ’80s. Since 1950, Yugoslavia had been under an economic regime called self-management socialism, which was something of a hybrid between Soviet Marxism and Western capitalism. With a one-party government, as in the Soviet Union, elections were purely ritual in character, and the state pulled the levers of many aspects of the economy. Unlike the Soviet system, however, the Yugoslav administration was highly decentralized, and workers were supposed to have a democratic voice in their places of work through workers’ councils. Small private businesses were allowed, and the economy was liberalized and opened up to international trade.

From the 1950s through the ’70s, the country had a high rate of economic growth and went through state-sponsored industrialization on a massive scale. The metal display system was successful product of the factories erected as part of this national push for industrial labor. Its existence is therefore anchored to the Marxist basis of the Yugoslavian economy and its valorization of collective work and social ownership.

However, as Akhøj learned from a small private metal dealer—a Bosnian Serb operating out of a garage in a far-off suburb of Belgrade—who said he used to produce the system in Bosnia until the war broke out, the system was not originally Yugoslavian: it had been mass-produced in and imported from China in the 1970s, and had become so popular that Yugoslav manufacturers started making it themselves. The trade deals that brought the display system to Yugoslavia, however, eventually developed into a much more fateful and sinister role for China in the region: during the Balkan Wars, it was the only country who supported and traded with Slobodan Milošović’s oppressive regime.

Long before China became a trading partner, Europe and the US exerted substantial commercial and cultural influence on Yugoslavia. The development of a robust Western-style consumer culture was allowed and even encouraged by the political class, in tension with the country’s socialist foundation. The display system, used to show off wares in both high- and low-end retail, became an unassuming but basic part of this culture of consumption, and, as such, had a minor role in undermining the Marxist industrial system that produced it. By the time it came into use in the late ’70s there was an economic crisis afoot, but advertising and retail displays continued perpetuating a consumerist fantasy that eventually proved unsustainable and socially divisive, as inequalities aggravated the nationalist tendencies that brought about the collapse of the federation in the 1990s.

While out in Belgrade one day in 2010, Akhøj spotted the display system through the windows of an upscale store, one of several owned by Jugoexport, a large state-owned import-export company that for decades occupied an ornate building on Republic Square, and which makes for a salient example of the ultimate collapse of Yugoslavian consumerism. After trying to cater higher-earning clientele for decades, Jugoexport went bankrupt around 2010. When Akhøj stopped in front of its shop on Republic Square, it was bolted shut. The chrome display system was standing empty amid cluttered cardboard boxes, fronted by unclothed fabric mannequins gathered haphazardly at the store’s window.

On his last trip to Belgrade, in July 2018, Akhøj made contact with a man who used the display system to build exhibition infrastructure for the entire Belgrade Fair (Beogradski Sajam). From the ’70’s until the late ’90’s, he kept his stock of parts in storage underneath the fairgrounds. Designed by the architect Milorad Pantović and constructed between 1953 and 1957, the Fair was an architectural feat with ideological import. It was built to replace the old fairgrounds, which during WWII had been used by the Nazis as a concentration and extermination camp, and was originally composed of three colossal domed halls of reinforced concrete connected by covered galleries and open-air walkways. Its innovative engineering and dynamic forms were seen as a break with the country’s political and architectural past, and it was considered a harbinger of the great things its renewed society would achieve.

For a long time, the display system participated in the realization of the national project that was inaugurated by the construction of the Fair. It displayed the products and professional achievements of the country during national fairs, and facilitated its exposure to foreign goods during international fairs. These activities came to a halt during the war. By the time Akhøj made it to the fairgrounds, the man who used to supply the displays had already given most of his stock away.

During an earlier visit, in 2010, Akhøj learned from the same metal dealer who told him the system originated in China that it was also known by the name Abstracta. Unlike Salamander, Investa, and the others, this name finally yielded results when Akhøj searched for it: it turned out that the Danish architect Poul Cadovius produced his own modular display system, also called Abstracta, in the early 60s, which turned out to be the prototype for the Chinese and Yugoslav models. It had, however, gone through a small yet significant adaptation on its journey: the latter models are one millimeter thicker in diameter—20 instead of 19—than Cadovius’ original.

At the age of 99, Cadovius was still alive at the time (he died in March of 2011). Upon returning to Denmark, Akhøj visited him and his wife, Evy, in their home in Funen and learned about Abstracta’s beginnings while sitting in chairs shaped like Abstracta joints. Cadovius founded his company in 1945 to manufacture his famous Royal System, one of the world’s first wall-mounted shelf systems. As he travelled to fairs to exhibit it, he found the available display structures lacking, which gave him the impetus to create Abstracta. But Cadovius quickly envisioned a much wider array of potential functions for his new invention, and he marketed it as a flexible furnishing solution for homes and businesses. He also created a modified version of the system for the purpose of constructing geodesic-style domes, or “bubble houses,” as he called them. He believed Abstracta could be used to build anything, even bridges, and that Abstracta domes could radically disrupt the construction methods of the time. By 1963, he considered it his most important invention to date.

Abstracta, however, didn’t become a commercial success in Denmark. In 1968, American businessman Charles Mauro made an agreement with Cadovius to market it in a simpler version, which he called “Cube in a Tube.” It also fell flat, but he donated a module to the design collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It’s still in the museum’s archives in Queens, listed as designed by Mauro and manufactured by Cadovius.

Until Akhøj’s visit, Cadovius was unaware of the unofficial success Abstracta had in Yugoslavia and China.

Over the years, Kasper Akhøj has collected a motley assortment of Abstracta parts and has used mixed batches of them to assemble new structures. Production differences among manufacturing facilities have meant that not all the parts are interchangeable, so his work entails finding matching ones. By leaving some of the modules incomplete, Akhøj creates a kind of visual phantom limb phenomenon, leading the viewer to complete the missing structure in her mind—a cognitive process analogical to our tendency to create coherent narratives out of the fragmented and often illogical movements of history. Akhøj’s removing the modules from circulation as display tools allows them for the first time to become artefacts worthy of display in their own right, and turns our awareness to the very logic of display—the power of forms to direct our attention, organize information, and render something more valuable than it would be were it not “on display.”

Akhøj’s process is also illustrative of the tension inherent in the promise of modularity: Abstracta was not only created to be connected and built, but also to be disconnected and dismantled. This flexibility allows its modules to be recycled and reshaped, and to lead multiple lives, but it also makes their existence precarious. This fact, together with the history embedded in the structures Akhøj produces, imbues them with ontological instability and, by extension, turns them into symbols for the vulnerability of artistic agency: as Abstracta’s fate ultimately eluded Cadovius’ control, the fate of Akhøj’s work—and of works of art in general—is ultimately not in its originator’s hands.

– Ronah Sadan