In 1921, Poul Henningsen and Axel Salto participated in the Efterårsudstilling (Artists’ Autumn Exhibition) at Den Frie. The exhibition was composed of ten installations, each made by an architect and an artist collaborating together to create their ideal room. This was a new idea by the architect Thorkild Henningsen, who was the creative force behind the exhibition. Among the other participating pairs were Kay Fisker with Mogens Lorentzen; William Scharff with Ivar Bentsen; Vilhelm Wanscher with himself; Th. Henningsen with Svend Johansen; and Vilhelm Lundstrøm with PH. Salto and PH created what by several accounts was the most exciting and original room, and it was an important moment in their young careers.

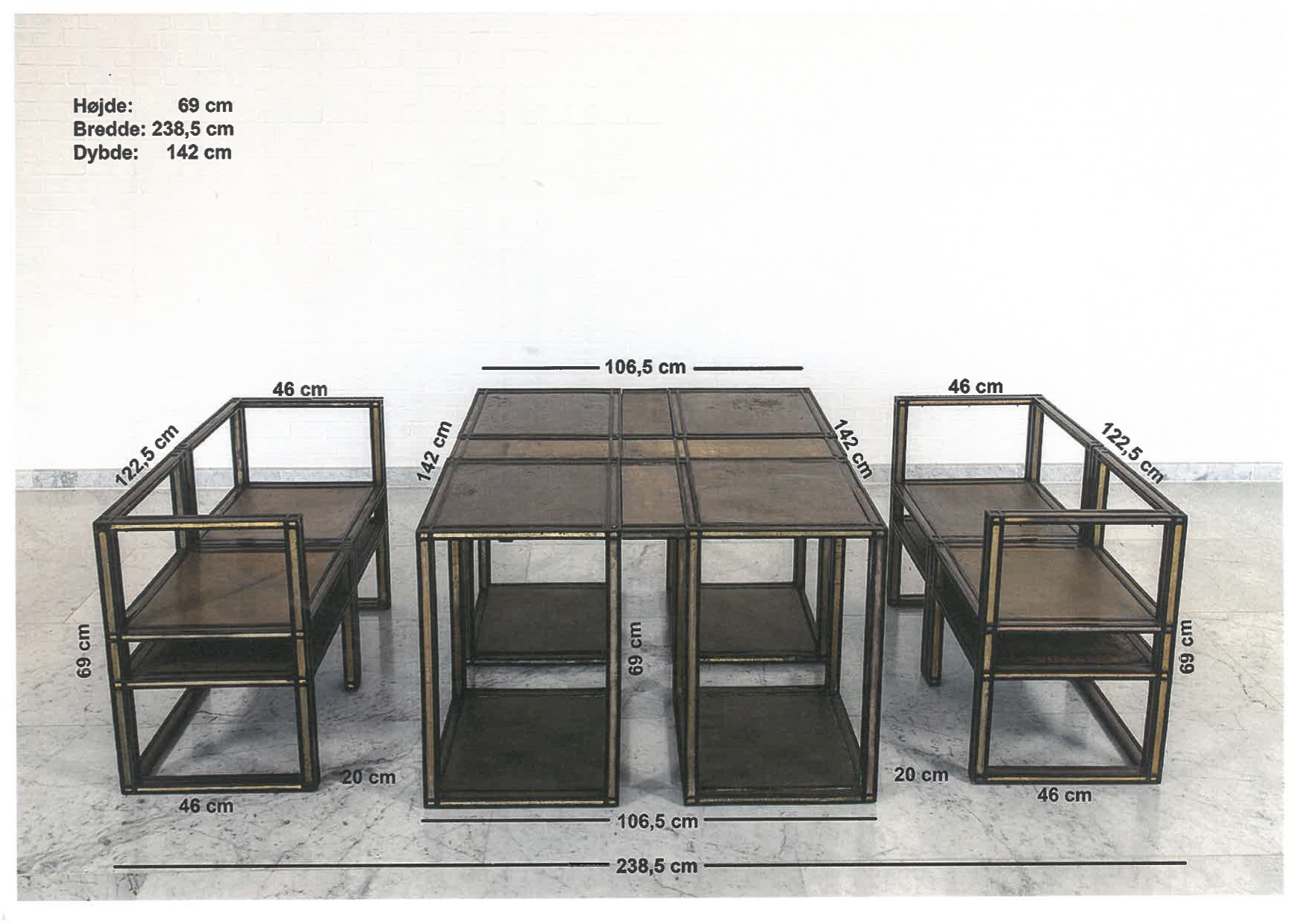

According to PH’s own description in the exhibition catalogue, the room was supposed to be a “view pavilion,” “situated on a high place with a free horizon,” where vista would be visible through four glass doors merging with skylights that crossed the ceiling (mirrors were used at Den Frie to approximate the effect). The furnishing consisted of an almost square table of black wood veneered with brass, the proportions of which matched those of the floor pattern—a grid of red lines with black insets, made of linoleum. The floor design, in turn, mirrored the structure of the skylights above, such that all lines and forms corresponded to each other with meticulous geometric precision.

Salto’s contribution, which consisted of eight large wall paintings and four smaller ceiling paintings (all done on linoleum panels), flanked the room’s corners and provided a counterpoint to the room’s pure angularity. With kinetic, variegated brushstrokes, they depicted scenes from the myth of Phaeton, the mortal son of the sun-god, Helios, who insisted on driving his father’s sun chariot and lost control of it, to disastrous consequences. Salto was fascinated with the story’s representation of nature’s dangerous and irrepressible energy—a fascination that drove his art practice throughout his life—to which he gave form by showing the unruly sun-chariot horses galloping as though driverless, their speed and fierceness almost pulsating through the paint. The pavilion’s combination of Salto’s stylized, expressive imagery and PH’s strict, reduced geometry thus presented the Danish public with two different facets of modernity combined into a surprisingly harmonious whole.

With its mythological theme and monumental composition, Salto and PH’s pavilion seems more like a temple or shrine than a room in a mansion, as one reviewer described it. Were it built in PH’s described ideal circumstances, the sun would have appeared through the windows to take its rightful place in the room’s formal and symbolic arrangement. Its movement would have also animated the room, by turns dramatically illuminating or obscuring Salto’s paintings, and throwing ever-changing patterns of shadows through the window-frames onto PH’s linear design. In the sun’s absence, PH installed one of his earliest multi-shade lamps: a spherical pendant made of silver-plated discs held together by steel wire, which looked from a distance (at least in photographs) as though they were floating above each other in space. Emitting glowing rays of light and casting striped shadows about the room, the lamp was cast in the role of the sun to Salto’s Phaeton.

It may seem as though the whole ensemble of the pavilion was made for purely theoretical purposes, and had no functional destiny. The table and lamp were, however, were originally made for the dining room of Inger and Kaj Kragelund, PH’s sister-in-law and her husband, who had recently moved to a new apartment in Aalborg and asked PH to help them decorate. The table was part of a set that included four matching chairs, and, as in the pavilion, it was matched to a gridded linoleum floor. The furniture had some practical limitations: the chairs were (somewhat unsurprisingly) uncomfortable, leading PH to throw black-and-white calfskins on them; and the sun-lamp, with its striped, glaring light, was also unsuitable for a domestic space, and was eventually exchanged with PH’s three-shade frosted glass pendant with spiral decoration designed by Salto.

Prior to the Efterårsudstilling, Salto was also involved in the decoration project for the Aalborg apartment: he made a porcelain dining set with rust-red edges and small decorations—one of his first known ceramic works. After the exhibition, his murals were given space in the dining room, where they remained until Inger Kragelund gave them, together with PH’s furnishings, to Kunsten Museum of Modern Art in Aalborg (then Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum) as a gift upon its opening in 1972, where they are still on display today.

The combined projects of the Kragelund apartment decoration and the 1921 Efterårsudstilling’s pavilion gave the young PH and Salto the opportunity to make foundational forays into the fields that would end up defining their careers—illumination and ceramics, respectively. They also gave them the chance to refine their aesthetic and theoretical approaches in a way that was decisive for their practices: for PH, it was an early exercise in his lifelong quest to balance functionality and beauty in his designs; for Salto, it was an ambitious illustration of nature’s power through the prism of Greco-Roman mythology, which he continued to refine in his ceramics.

But it would actually be a shame to reduce this episode merely to its formative value, placing it in the shadow of PH and Salto’s subsequent achievements. The pavilion was a complex and compelling formal and conceptual composition in its own right, and it was at the avant-garde of Danish art and design in the 20’s. Its constitutive parts then had a long life of active use at the Kragelund apartment, which endowed them with further layers of no less important cultural and social meaning.