Galleri Feldt has in its collection an easy chair and two footstools designed by Grete Jalk for her stand at the 1963 Cabinetmaker’s Guild Exhibition, in which she made a historic yet little known contribution to the world of interior design: she presented the public with a new conception of what leisure in the domestic sphere could look like. This unconventional success came on the heels of Jalk’s winning an international design competition for a gendered husband-and-wife chair set that received quite a bit of attention in Denmark and abroad. Through both of these projects, Jalk used design to touch on social phenomena in a way that, though innovative and forward-looking, was complexly ambivalent and, with hindsight, hard to pin down. What’s certain is that her designs, though very much of their time, are unquestionably relevant to today’s urgently debated issues surrounding gender roles and the role of technology in our daily life.

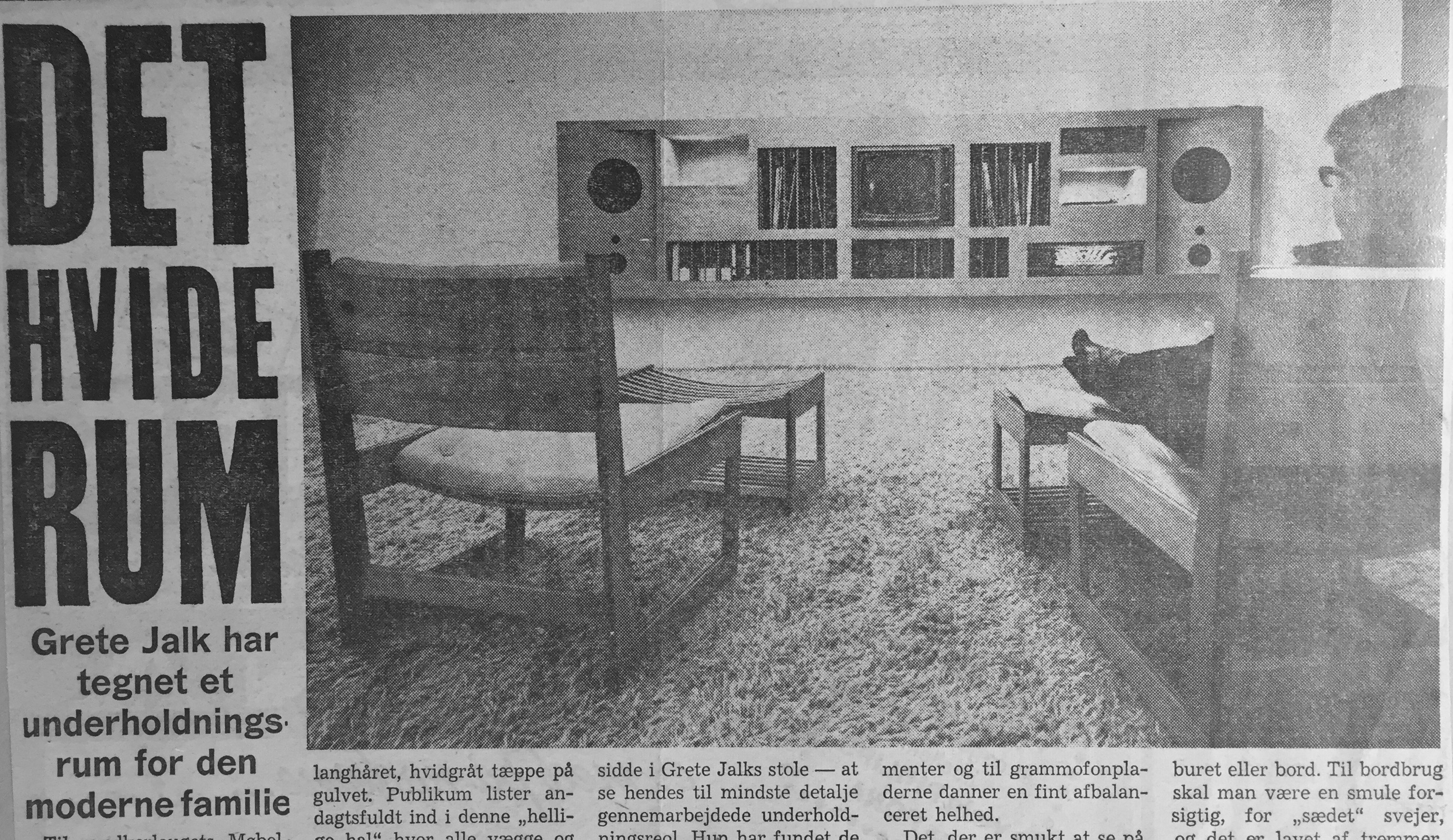

Jalk’s 1963 Exhibition stand consisted of an undecorated white room in which Galleri Feldt’s chair stood with a footstool on a shaggy gray rug beside an identical seating set. Made by cabinetmaker Henning Jensen, the chairs were sled-based and made of Oregon Pine and Nigerian leather, with a low-lying, angular form whose boxyness is attenuated by a narrow base and softly curving seats and backrests. Together they stood facing a wall with an in-built unit also of Oregon Pine (likewise made by Henning Jensen), which included cubbies and shelves custom-built for a home-entertainment system: a gramophone, radio, stereo, tape recorder, record player, loud speakers, an amplifier, space for tapes and records and, centrally placed, a television set. To achieve the best sound quality possible, Jalk had the walls and ceiling covered in acoustic fabric, and had the sounds of pop and classical music waft through the air. Called “entertainment wall for the citizen of the Affluent State,” the wall unit unveiled and aestheticized—to a degree quite possibly unseen before—the future locus of attention in the lives of those who could afford it: an infrastructure for absorption into sound and moving image.

In creating her unit, Jalk took on a task that many designers before her had shunned. In the early 60’s, the popularization of the television set presented an unsought-after challenge of integrating the widely considered ugly new technology into the traditional arrangement of the living room. The problem was actually more than aesthetic: the boxed screen interfered with the very concept of the communal home space, in which people through much of history had nothing more engaging to face and listen to than each other. The radio and gramophone had already altered this landscape to some degree, but new audio equipment such as loudspeakers was considered something that should be as little seen as possible. The solution was screens, curtains, partitions—anything that could obscure the presence of the new devices in the home.

Jalk’s exposing and organizing these devices in a streamlined, attractive way was considered a surprising success. Reviewers remarked on the fact that “the radio and television set are not concealed behind tambour doors as though they were in some way odious,” and were struck that Jalk chose the most “acceptable” appliances available and that “the compartments for the technical equipment and for the records form a beautifully balanced whole.” Visitors to the stands reportedly “tiptoe[d] into this ‘hallowed spot,’” a place that managed to transform the aversion many felt towards home entertainment technology into reverence.

However, Jalk’s apparent proselytizing for this technology came with what appears like a subtle caveat hinted at in the name, “entertainment wall for the citizen of the Affluent State,” which is a translation of the Danish, velstandssamfundets underholdningsvæg. The term velstandssamfundet,—the Affluent State—is a play on velfærdssamfund—the welfare state—a concept that lies at the heart of Danish self-understanding, and is based on the idea of solidarity among citizens and equality in access to healthcare, education, and social security. Jalk’s velstandssamfundet appears to stand for nothing but material wealth, and has none of the connotations of social justice and well-being included in the term velfærdssamfundet. It hence sounds self-critical, because it suggests that her entertainment wall belongs to a world devoid of some of Denmark’s most cherished values; a world of social atomization in which solidarity is replaced by appliance-driven absorption, and wealth production via consumerism is the ultimate goal. But this ironic tenor is most likely a contemporary projection on Jalk’s original intention, which was an aspirational one, showing the technological and cultural possibilities of prosperity. Jalk must have at least acknowledged, though, the fact that her entertainment wall was beyond the financial reach of most Danes, and that it custom-fits itself into an exclusive reality that could perhaps become a more common standard in the future, depending on how broadly the prosperity of the Danish economy would spread itself.

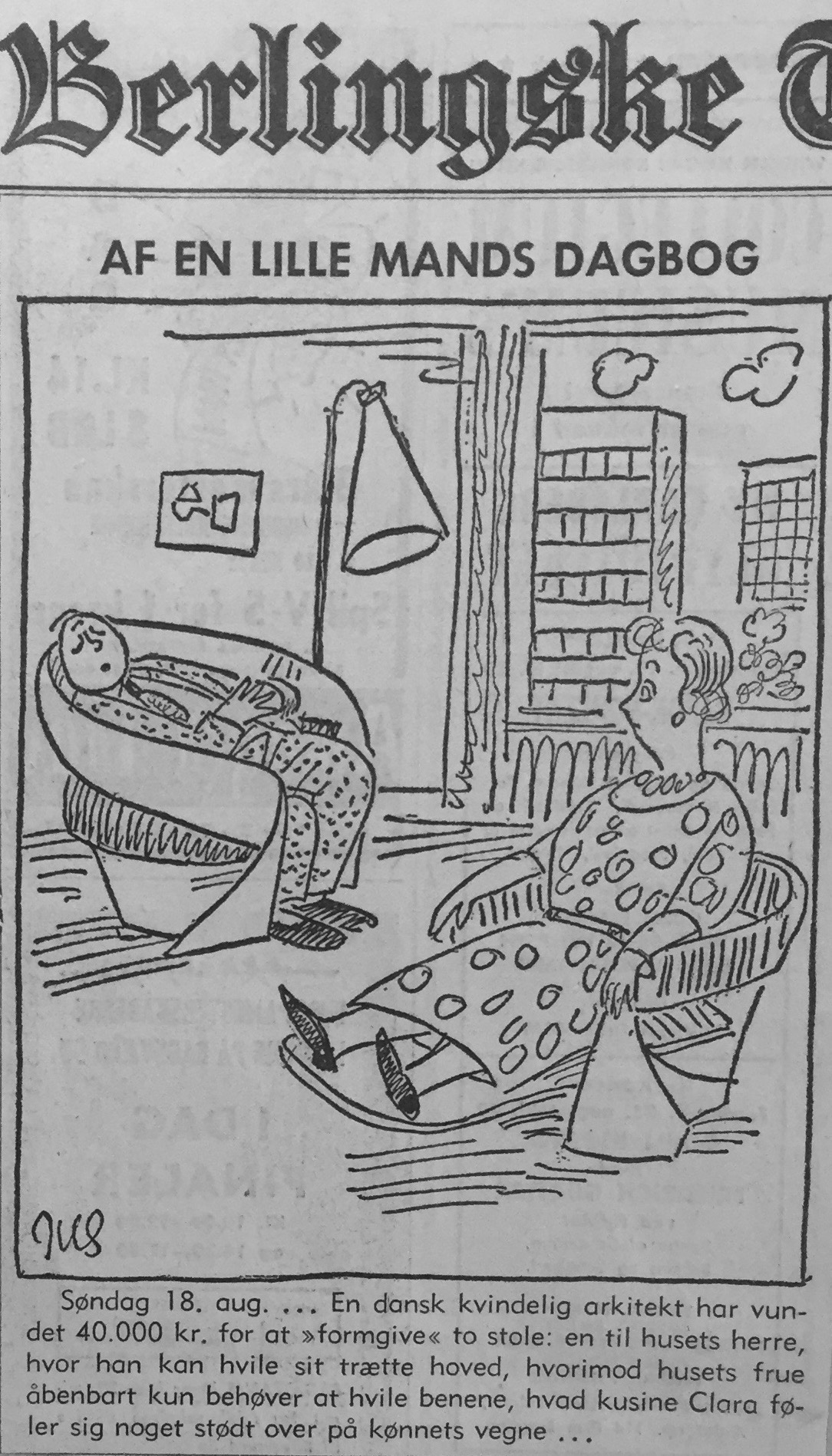

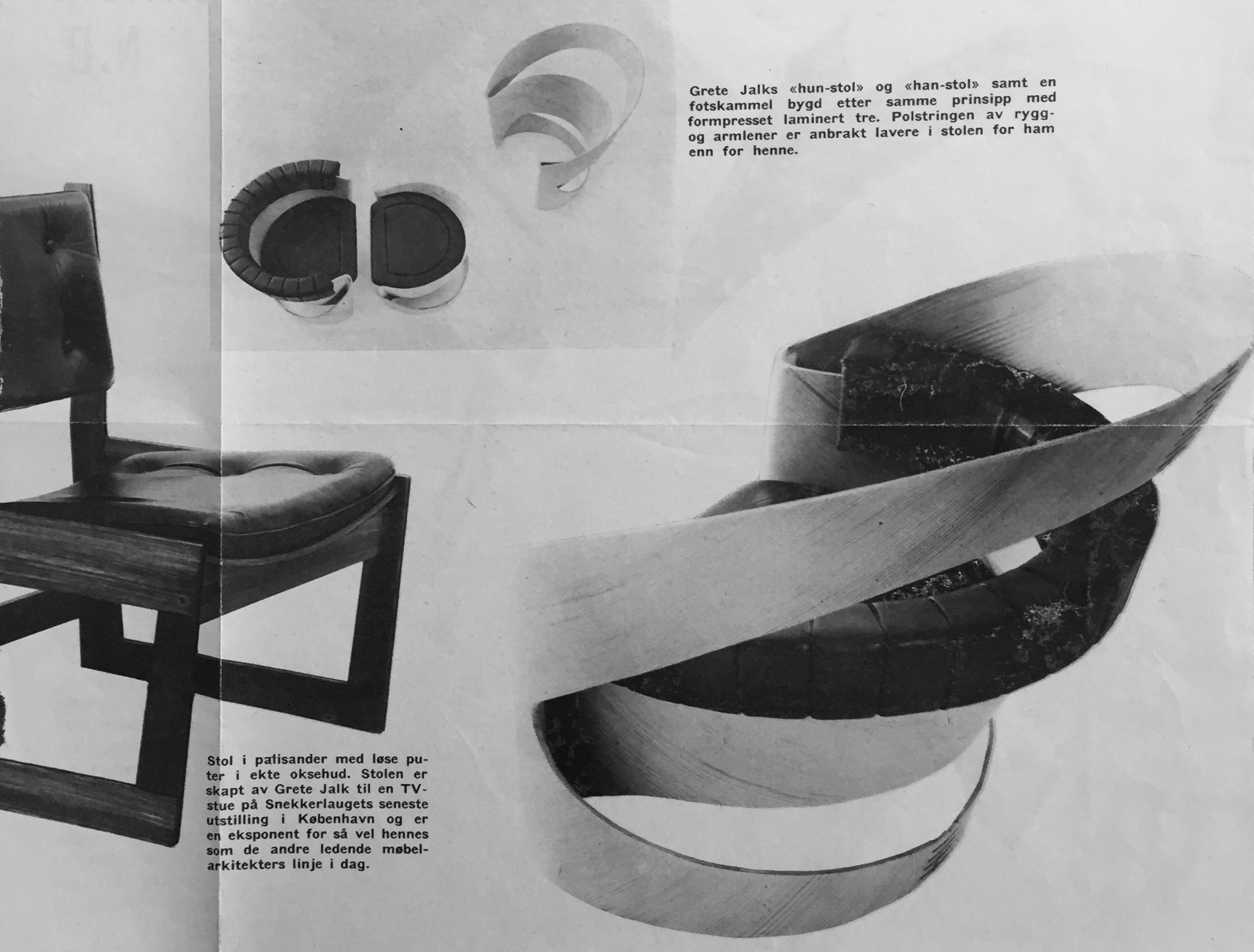

Earlier in 1963, with her winning entry for the Dail Mirror’s International Furniture Design Competition, Jalk created another design that was futuristic looking, but in contrast with the “entertainment wall,” was very much descriptive of the present. The “arkitektpige” (or “architect girl”), as she was called in the Danish press, designed a pair of matching easy chairs for a married couple, each tailored for the needs of the husband or wife. The “he-and-she” chairs were exceedingly modern, constructed of a shell of molded plywood with cushioning of leather-covered rubber foam, and their difference rested in the back support: the woman’s was low, allowing for the seater to lean only up to the mid-back, while the man’s included a support for the head, allowing for a full-body lean. The she-chair was, however, provided with a matching footstool, while the he-chair lacked.

The structures of the chairs, though cutting-edge in their materials and forms, seem to reflect traditional gender roles, according to which men carried out cerebral activities while women performed housework. As a French magazine explains in its review of Jalk’s chairs, “for reading a journal or for knitting, one does not sit in the same manner,” and concludes, approvingly, that Jalk’s chairs correspond to the masculine and feminine “ideals.” A cartoon in Denmark’s Berlingske newspaper evinces a more skeptical viewpoint. It pictures a living room with a man napping in the he-chair, his head comfortably propped by the headrest, while his wife sits stiffly upright in the she-chair and observes him with a bemused expression. The caption reads, “A Danish woman architect has won 40,000 kroner for ‘designing’ two chairs: one for the master of the house, where he can rest his tired head, whereas the mistress obviously only needs to rest her legs, which cousin Clara feels somewhat offended about on the gender’s behalf….” (It is unclear who “cousin Clara” is, but in any case, lest the reader draw a feminist-leaning lesson from the cartoon, the quotation marks around the word “designing” telegraphs the cartoonist’s disdain for Jalk’s work.)

As with the velstandssamfund’s entertainment system, it is difficult not to anachronistically project a political intention onto Grete Jalk’s he-she-chairs, which, as the Berlingske cartoon indicates, even in her day was construed by some as insultingly gendered. Did she—a woman who broke norms by rising to prominence in a distinctly male profession—mean to provoke this discussion on gender norms? Are the he-and-she chairs a tongue-in-cheek commentary on social conventions? Or did she, like her approving French critic, see women’s role in society and the home as limited and unequal? There is an ambiguity here that is hard to parse, but it is nevertheless difficult to imagine that Jalk would design something totally subversive of the order to which it caters.

It seems more likely, in the case of the he-and-she chairs, that the very idea of designing an armchair with the specific needs of women’s comfort in mind, recognizing the reality of their work, was a progressive gesture. In fact, it came from Jalk’s own experience as a working woman. In an interview, Jalk explained her choices with a neither distinctly feminist nor conservative angle, saying, “I myself very much like to raise my legs when I sit in a chair, so I figured that other women would, too.” In the long history of gendered chair design—for centuries, women’s chairs had very low or no armrests (to facilitate sowing), and the back-rest was often slanted so that it wouldn’t touch the sitter’s corset—this was probably one of the first instances of empathy-driven decision-making. Unfortunately, Jalk’s he-and-she set was never slated for production, so we don’t know how sitters would have fared in practice.

However one reads Grete Jalk’s designs today, it is hard not to be impressed by the way she had her finger on Denmark’s cultural pulse, as well as by the generosity of her formal imagination. Her designs amount to enormously creative responses to social realities, and for that she deserves far more thoughtful recognition than she currently receives.